Articles & Insights

The Two-Minute Rule

January 5, 2026

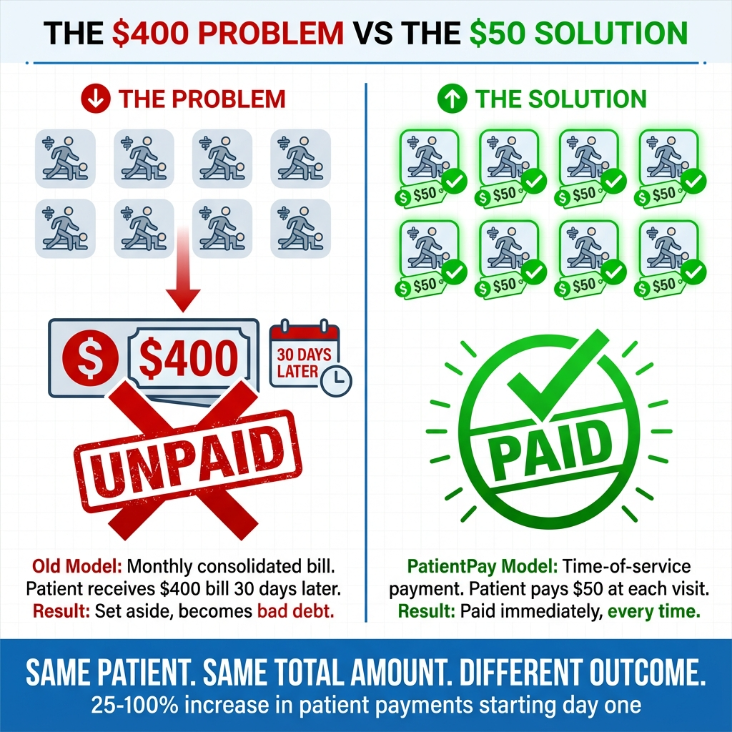

Physical therapy medical groups and chiropractors using PatientPay have noticed something counterintuitive. Patients who previously ignored large monthly bills now pay reliably when charged smaller amounts at each visit.

This isn't coincidence. It's not better patient behavior or improved collection tactics.

It's better billing design aligned with how human psychology actually works.

Patient payments now represent nearly 35% of total provider revenue, a figure expected to increase in the coming years. With that shift comes a critical question: why are so many medical groups still struggling to collect?

The problem isn't that patients can't pay. It's that the billing model creates unnecessary friction.

Consider the typical scenario: a patient receives physical therapy twice per week for a month. At the end of that month, a $400 bill arrives in the mail covering all eight visits. The bill feels large. The patient sets it aside. Eventually, it becomes bad debt.

Meanwhile, medical groups are drowning in collection attempts. The typical medical group must send an average of 3.3 paper statements before payment is secured. And with 63% of healthcare providers reporting staffing shortages in revenue cycle departments, there's simply no capacity for endless follow-up calls.

The traditional approach isn't working. But there's a reason why, and it's rooted in behavioral science.

Every payment activates the same brain regions associated with physical pain. This phenomenon, first coined by behavioral economist Ofer Zellermayer and later popularized by researchers like Dan Ariely at Duke University, is called the "pain of paying."

Here's what matters: larger payments create proportionally more psychological discomfort. That discomfort triggers avoidance behavior. Patients don't ignore bills because they're irresponsible. They avoid them because the psychological pain is real.

Smaller payments register as less painful. They're easier to complete without resistance. A $50 charge feels manageable. A $400 bill feels like a financial event requiring deliberation.

This isn't just theory. It's observable in medical group after medical group that has switched to time-of-service payments.

Nobel laureate Richard Thaler won the 2017 Nobel Prize in Economics partly for his work on mental accounting: how people categorize money differently based on context.

A $50 payment today feels like one discrete transaction. It's contained. It's complete.

A $200 bill covering four visits feels like something entirely different. It's a larger financial event. It requires mental deliberation. Patients ask themselves: Can I afford this right now? Should I wait until next paycheck? Maybe I'll deal with this later.

"Later" often becomes "never."

When payment happens at the time of service, patients perceive it as a fair exchange. They just received care. They know what they're paying for. The value is clear and immediate.

When a bill arrives weeks later covering multiple services, something changes. The connection between value received and payment owed becomes abstract. Patients forget the specific details of their visits. The bill feels disconnected from the care experience.

This is called the decoupling effect. Consolidated monthly billing decouples the payment from the care experience. By the time the bill arrives, the positive experience of receiving treatment has faded. What remains is just a number on a page.

Time-of-service payment keeps the transaction coupled with the moment of care. The patient walks out feeling better, pays a manageable amount, and the transaction is complete. No lingering bills. No avoidance behavior.

The behavioral economics framework isn't just academically interesting. It produces measurable results.

Hospitals implementing time-of-service payments through PatientPay see 25% to 100% increase in patient payments from bills starting day one, with payments beginning within two minutes of sending the bill.

This pattern holds consistently across recurring-visit medical groups: physical therapy, chiropractic care, behavioral health. The model works because it respects how people actually make payment decisions.

Let's return to our physical therapy example:

Old model: $400 bill arrives at month end covering 8 visits. The bill feels large. Patient sets it aside. Eventually it becomes bad debt.

PatientPay model: $50 charge at each visit or the bill is generated immediately upon claim adjudication. Patient pays without friction because the amount feels manageable and directly connected to care just received.

Same patient. Same total amount owed. Dramatically different outcomes.

Only 17% of consumers receive medical bills electronically, despite over 70% preferring electronic statements. That gap represents missed opportunity.

Patients want convenience. They want transparency. They want to pay in ways that they feel manageable and fair.

When medical groups align billing with those preferences and with behavioral psychology, everyone benefits.

"When patients understand their financial responsibilities and feel more in control of their healthcare payment experience, it is a win-win-win equation for them, the RCM and the healthcare provider." — Tom Furr, CEO, PatientPay (Source)

Here's what this approach is not: it's not about collecting more aggressively. It's not about squeezing patients or creating financial pressure. It's about aligning payment timing with how human psychology actually works.

Smaller, timely payments feel fair to patients. They reduce psychological resistance. They keep transactions connected to the value received. And they protect medical group revenue without adding burden to already stretched revenue cycle teams.

When you respect behavioral economics, everyone wins. Patients feel in control. Medical groups get paid predictably. Staff aren't buried in collection calls chasing months-old bills.

The science is clear. The results are consistent. The question is whether medical groups will continue using a billing model designed for administrative convenience or switch to one designed around human behavior.

Because the $400 problem doesn't require more collection attempts. It requires rethinking when and how we ask patients to pay.